|

We live in a pretty competitive environment for kids. I have noticed lately that whenever I meet new people, or even when I am with my friends, the following question arises, "What's your kid into?"

The answer to this question is not meant to be Mine Craft or Lego or American Girl dolls. People are talking about travel soccer, elite swim teams, competitive gymnastics, and many times per week ballet lessons. My kids don't do any of these things. They do a lot of stuff -- they play instruments, they play sports, they go to religious school, they do some theatre. But, they do all of these activities once per week. They aren't tremendously talented at any of them. They certainly aren't destined for Broadway or the Olympics (so far as I can tell). As one of my dear friends said a few years ago as all of our girls were galloping around ballet class, "I guess if any of our kids were prodigies, we would know already!" In our home, we place a lot of focus on school and also on education outside of school (through travel, exposure to culture like museums, concerts, etc.). We view the rest of these activities as "icing on the cake". I've noticed lately, however, that when people discuss what their kids are "into," it brings up a lot of emotion for me. A little anxiety, a little frustration, a shade of sadness.... On the one hand, I worry that I haven't pushed my kids hard enough. Should their tennis lessons be less fun and more focused on the game? Should we amp up the sports to travel teams? Should my daughter who is good at theatre be doing theatre all year round instead of just over the summer? Should she have a vocal coach and a dance coach? Ah!!!! But then, I take a step back. With school and the relatively limited activities we do, there is barely time for our kids to PLAY. Play is extremely important for young children -- building with Lego, playing make believe with dolls, doing crafts with materials available to them that aren't dictated by a specific assignment. In my clinical work, kids say all the time that they wish they just had more time to play -- and I think this is a statement we should listen to. Furthermore, while I believe there are some kids who do come to a true passion on their own at a very young age, I am angry by the idea that all is lost if our kids haven't found that passion before they hit the double digits. Is it possible that they have not been exposed to the activity yet that they are meant to love and excel at? Perhaps they haven't yet met a certain teacher or other influential adult who they want to emulate. Developmentally, they might not be ready yet to be an amazing lacrosse player or to be committed enough to play piano for two hours per evening after a full day of school. Isn't it okay if this hits in 7th grade or 10th grade? Here is my thought. As parents, I think all we can do is expose our kids to a wide variety of activities that we think they might enjoy. We should take their lead. If a child is very artistic, we should expose them to more art, rather than forcing them into sports because "everyone else does sports" or because it might get them into college. We should be responsive to our children saying they want to do more.....and be comfortable saying NO to coaches or teachers who are demanding more to the detriment or play time, social lives, or even sleep. And, we should be okay with our kids just liking lots of things, rather than having a specialty at a very young age. After all, variety is the spice of life.

0 Comments

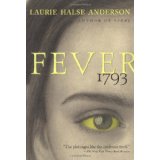

In my practice, I see a lot of really smart kids - it seems to go along with anxiety, for better or for worse. I am struck by how often parents and schools expose smart kids to information beyond their emotional capacity. Kids who are really bright can inadvertently trick us into assuming that they can emotionally process very difficult information. But, a smart nine year old is still.....NINE. An example of this has hit my house these last few weeks. My daughter is a 4th grader, and is in her school's gifted program. It is a wonderful program and we are grateful that it exposes her to like-minded kids who love to learn and to in-depth learning about focused topics - something that is not often done in the regular classroom. This semester's topic, however, has been very challenging. The children are studying the yellow fever epidemic that affected Philadelphia in 1793. Their learning began with a very vivid film that included those affected vomiting black fluid, and a small girl burying her dead mother. Apparently, most of the kids in the class were in tears during this film. When we discussed it at home, it became very clear to me that my very smart daughter thought the people in the film were real. She completely identified with the little girl whose mother died and she felt absolutely devastated for her. She was horrified by the blood, black vomit, and yellowed eyes. I posed her the following question -- "Were there video recorders and TVs in 1793?" A moment of realization came across her face. She said, "Oh mommy, they were ACTORS!" Yes, they were actors. But, did any of the children recognize this? Or, did we grown-ups assume that these super-smart kids "got it" and could process the content like we could? Given how upsetting the film was, I decided to read along with my daughter as they read the book, "Fever 1793" by Laurie Halse Anderson. As a psychologist working with anxious kids, I have to say this book is horrifying. For my adult self, it is very well written, interesting from a historical perspective....but still horrifying. I can't imagine that 9 and 10 year old kids, even gifted ones, can process the idea of half a city dying from a contagious illness; children losing every family member and being orphaned; or a 14 year old having to ward off invaders in her previously safe and loving home. Could the children learn about the yellow fever epidemic in a different way? Sure. They could learn about the immune system and vaccines and how such epidemics can't happen anymore (yes...I know what you're thinking....Ebola, measles, but we are talking to kids here, so let's keep it simple!). They could learn about the racial issues affecting Philadelphia at the time and how they played into this public health crisis. They could learn about what life was like in Philadelphia at this pivotal time and how different factors made the spread of disease so likely (ie., what were bathrooms like, what was the water supply like, where did people get their food from, how hard was it to get out of the city given that there were no cars or trains or taxis)? I am not saying that we shouldn't expose kids to emotion or to difficult topics -- but we need to be mindful of their developmental level and how it might not match up with their scores on tests or on how articulate they are. |

Dr. LedleyI am a licensed psychologist working with kids, teens, and adults with anxiety disorders. Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed